EXTRACT 5 FROM MY MEMOIR

The Spy who Fell to Earth: My Relationship with the Secret Agent Who Rocked the Middle East

CHAPTER 3: SPYING

THE MOSSAD, THOUGH, WERE STILL cautious. The Israelis had to be sure Marwan was not playing a double game and was not a deceiver. And they had one surefire way to do so: to weigh what he gave them against what they received from another agent deep within the Egyptian establishment. This agent - whose identity is still a state secret - was an Egyptian army officer controlled not by the Mossad but by Israeli Army Intelligence and provided superb information, particularly on the southern sector of the Egyptian front and other more general matters. And when the Mossad weighed, with painful care, the information they received from their two Egyptian spies, they concluded that Marwan was the real deal and that they had hit a gold mine, as was vividly demonstrated in 1971.

In August of that year, Marwan handed over to his Mossad control, Dubi Asherov, one of Egypt’s most closely held secrets - her top-secret war plans. It outlined how five Egyptian infantry divisions, supported by armoured brigades, would cross the Suez Canal using small boats and bridges, establish a foothold on the east bank of the Canal, and from there move deeper into the Sinai desert to liberate it from Israeli occupation. Marwan’s information also included detailed maps and transcripts of high-level Egyptian-Soviet meetings - the Soviets were the patron of Egypt at that time. Marwan did something else too: he explained and interpreted the documents to the Israelis. The latter oral explanation was filed by Mossad under the heading, `The Evaluation of the Source,’ the `Source’ being Ashraf Marwan, whose name was not spelled out in order to protect him. Marwan’s evaluations focused on a range of military and political matters, as well as general subjects such as the Egyptian economy, education, top appointments to key posts in the Egyptian administration, and gossip. Trusted by his direct boss, President Sadat, Marwan was often dispatched as the president’s representative to key meetings, notably of the Egyptian military high command, and straight after these meetings, he would provide the Israelis with transcripts of what happened, and he would also describe the atmosphere in these gatherings. For Israel, with Marwan’s information under her belt, Egypt had become an open book; as a Mossad operator who often read Marwan’s reports once put it, `having Marwan as a spy was like being in bed with President Sadat.’

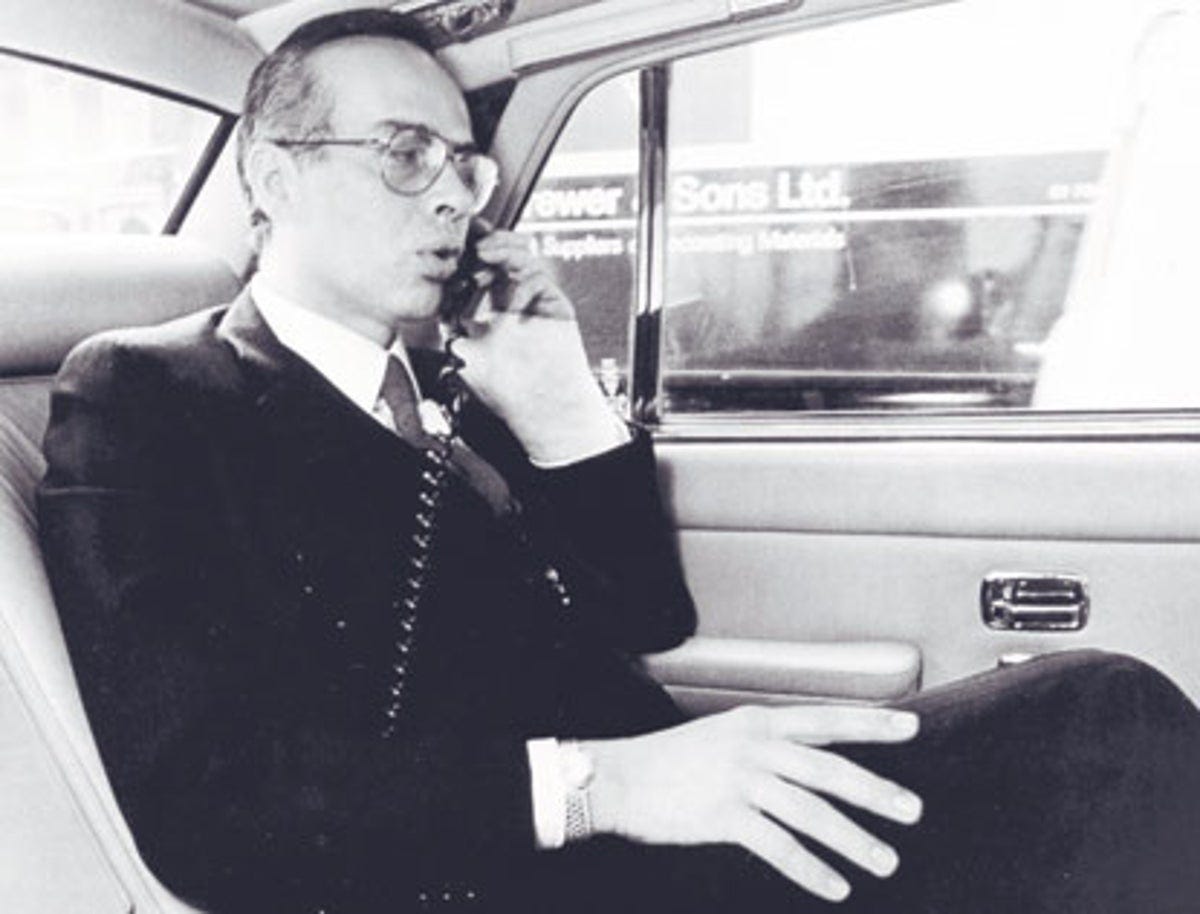

Secretly filmed: a meeting between Marwan (right) and his handler

As Marwan’s reputation grew, the Israelis, who regarded him as such a miraculous source, recast their entire thinking about the probability of war with Egypt, exclusively on the basis of Marwan’s documents and his oral explanations and interpretations. This new thinking became known as `The Conception’.

Rivers of ink have been spilled over the Israeli `Conception,’ but in fact, it is quite simple: at its heart was the understanding, based on Marwan’s information, that Egypt would not wage war against Israel without first acquiring from her patrons, the Soviets, certain weaponry, namely fighter bombers with a capacity sufficient to drop large bombs on Israeli cities, and Scud missiles to deter the superior Israeli air force from attacking Egyptian centres of population, lest Egypt retaliate in kind. Additionally, Egypt would not launch a war against Israel on her own without direct Syrian participation, too, as only simultaneous attacks from south and north, could defeat Israel by obliging the Israeli Defence Forces to be split and thus weakened in order to face assaults on two fronts.

Adhering to the `Conception’ meant that, practically, all Israel had to do was monitor Egyptian airbases and other entry points into the country for evidence that these weapons, aircraft, and missiles—Sadat’s precondition to attack Israel, according to Marwan—had arrived in Egypt. So long as Egypt had not received the Soviet arms and aircraft, Israel could feel that it was safe from war.

Most of the meetings with his control, Dubi Asherov, were initiated by Marwan. The Israelis, though, assumed that the telephone lines of their London embassy were tapped, by either British or other intelligence agencies, so they set up a system whereby Marwan would not have to endanger himself by phoning the embassy directly. Instead, he was given the telephone numbers of two London Jewish ladies who were working for the Mossad, and whenever he wished to meet `Alex,’ he would phone one of them and leave an agreed code, which they then forwarded to Asherov. When the spy and his handler met up, it was in a plush safe apartment near the Dorchester Hotel, which the Mossad purchased in 1971 solely for talking to Marwan. Dubi Asherov often arrived at these meetings holding a suitcase containing thousands of banknotes, payment for Marwan’s services; altogether, Marwan would receive more than $1m from Mossad - a staggeringly large amount for an intelligence source. As Marwan and Asherov came to know each other better - they often met twice a month - the relationship between them became closer, even intimate, and they gave each other presents from time to time. Marwan loved guns, particularly small pistols, so he often brought them to the meetings, pointing them here and there; on one occasion, he gave Asherov a .38 Smith & Wesson pistol as a present. Asherov tried to dissuade Marwan from carrying guns, as even the British police did not carry weapons on the streets of London, but Marwan just laughed it off, saying to Asherov that `nobody, but nobody, touches Ashraf Marwan.’

The real gun Ashraf Marwan gave his handler as a present

This and other similar incidents reinforced the view in Tel Aviv that they had a problem: their top spy, Marwan, was reckless, and the problem was not only his obsession with guns but what seemed to be the most irresponsible behaviour. Often, he would arrive at meetings with the Mossad in a car belonging to the Egyptian embassy and carry a diplomatic number plate. On other occasions, he would phone the Israeli embassy directly rather than resorting to the arrangement of using the go-between service of the Jewish ladies. Some of the documents he brought to the meetings were not even copies but originals, stamped with security classification and numbered, which, of course, could risk his neck should anyone in Egypt find out that the documents were missing.

Concerned that the close relationship between Marwan and Asherov might hinder Asherov’s ability to control his spy efficiently, Zvi Zamir, director of Mossad, ruled that Asherov should introduce Marwan to a successor. The choice fell on a Syrian-born Mossad agent, a charming, well-built man and an experienced operator. But Marwan bridled and the idea was shelved, though not for long. A few months later, Zamir again instructed Asherov to introduce someone else, but this time round, not to tell Marwan in advance; Asherov would bring the replacement to the meeting and introduce him to Marwan there and then. The chosen man was an Iraqi-born Mossad operator, who waited in an adjacent room for a signal from Asherov to join the meeting. When he finally walked into the room, Marwan was taken aback and ignored the new man, who nonetheless tried to impress Marwan by talking to him in fluent Arabic, though with a hint of an Iraqi accent. When, later, the man left the room, Marwan turned to Asherov, complained about `this Iraqi guy,’ and then with an air of superiority, explained to Asherov that in the Arab world, there is a hierarchy: at the top are the Egyptians, under them the Syrians, then the Jordanians and the Saudis; as for the Iraqis, `they are at the bottom of the heap’. To emphasize his point, Marwan made a gesture of stepping on an insect. With the second failed attempt to replace Dubi Asherov, the idea of finding him a replacement was dropped for good, and to the end of his service with the Mossad Asherov - `Alex’ - would remain Ashraf Marwan’s controller.

In the meantime, Marwan had become so important to Israel that every care was taken to keep him happy. When Dubi Asherov learnt that relations between Marwan and his wife, Mona, were shaky, concerned that the couple might split and Marwan would lose his special `Nasser effect,’ the Israelis purchased a diamond ring in Tel Aviv, and Asherov asked Marwan to give it to Mona as a present. And with the Israeli faith in Marwan increasing, they promoted him from being a provider of information to a `warning’ agent, whose task would be to raise the alarm should an Egyptian attack on Israel become imminent. His handlers trained him to use a wireless transmitter so that in case of danger of war, he could send a quick message of warning that would be intercepted by an advanced receiver located at the Mossad’s headquarters in Herzliya, just north of Tel Aviv. It was a bulky gadget with black pushbuttons which Marwan did not like; if caught with it, he would be in danger of being hanged. So, he politely accepted it, but back in Cairo, he put the transmitter in a paper bag, walked down the Nile, and dropped it into the river.

Yet, even without the electronic device at his disposal, Marwan raised the alarm at least twice, warning the Israelis of an imminent Egyptian attack. He did so first in November 1972 and then again in April 1973. For the Israelis, both warnings were confusing, as on the basis of Marwan’s past information they only expected an Egyptian attack after certain preconditions were met, namely the arrival in Egypt of Soviet weaponry - and at the time of Marwan’s warnings it was known in Israel that Egypt hadn’t yet got the equipment. While in 1972, the Israelis did nothing with Marwan’s warning, in April 1973, when Marwan warned them again of an imminent war, they decided not to take any chances and ordered a massive deployment of forces to counter a possible joint Egyptian and Syrian invasion, as indicated by Marwan. But no attack came, neither in November 1972 nor in April 1973. And yet, despite these occasional errors, most of Marwan’s information was accurate, with the one he provided the Israelis in October 1973, being regarded as his most dramatic piece of information ever.

On 4 October 1973, from Paris, Marwan contacted his Mossad control `Alex.’ This time, he was careful not to phone the Israeli embassy directly; instead, he used the system by which he relayed a message through a lady in London, who then contacted the embassy with the code word for Asherov. Marwan’s message was that Asherov should wait for him to phone again. Upon receiving this message, Asherov rushed to a safe flat, where he waited for Marwan’s call. When they finally spoke, Marwan was brief and to the point. He said he wanted to discuss `lots of chemicals’ and see the `general’ in London the next day - a reference to the Director of the Mossad, Zvi Zamir, a former military general.

Ashraf Marwan in London in the 1970s - a businessman and a spy

Marwan was a chemist by training, and many of the agreed emergency code words the Israelis equipped him with came from the world of chemistry, as he would more easily remember them. Moreover, to anyone listening on the line, Marwan mentioning chemical substances would not be suspicious, seeing as he was a chemist. `Lots of chemicals’ was an agreed code for a warning of war, a notice that Egypt intended to attack Israel from across the Suez Canal. However, `lots of chemicals’ was a general, not a specific warning of war; it was not the most serious of warnings. Should Marwan wish to warn of an imminent or an immediate attack on Israel, then he had in his arsenal specific codes to do so. But Marwan’s request to see the director of the Mossad was unusual; true, they had met before in person, and Zamir, having such an important spy on his lists, had always been personally involved in handling him, but then all the previous meetings between Marwan and Zamir were initiated by the Mossad, not Marwan. However now, perhaps for the first time ever, it was Marwan who asked to see Zamir.

After putting down the phone, Asherov summarized his conversation with Marwan, contacted Mossad’s headquarters in Israel, and reported. Upon Marwan's request, he also summoned Zamir to London to meet the Egyptian.

While Marwan’s warning was not of an imminent attack on Israel, taken together with major Egyptian and Syrian movements of forces along the borders, which the Israelis had spotted but had done nothing about, it seemed to be more ominous. So Zamir boarded a plane and hurried to the UK to meet his most senior spy; in the meantime, Marwan himself departed Paris for London and checked into a suite on the eleventh floor of the Churchill Hotel, near Oxford Street.

FRIDAY, 5 OCTOBER, 10 P.M.

Zamir and Asherov wait for Marwan to arrive at the Mossad safe flat in Kensington, central London. The building is surrounded by ten armed agents, led by Zvi Malkin, an experienced Mossad field commander, to protect the head of their organization and, if necessary, to break in and rescue him. As usual, Marwan is late, and there is a lot of tension in the air. Once again, he seems to demonstrate an air of recklessness, as he arrives at the flat an hour and a half late, driven by a chauffeur in a car that belongs to the Egyptian embassy. Marwan has an explanation for his late arrival, though. He says he was held up at the Egyptian consulate in Kensington, where he tried to gather as much information as possible from Cairo.

Now Marwan goes straight to the heart of the matter; he has asked to see Zamir in person, he says, to issue him with a warning of an imminent attack on Israel, which will start in less than twenty-four hours, coordinated between Syria and Egypt. While Asherov takes notes, Zamir listens attentively. Can he trust Marwan? Marwan is the most important spy in his organization, but twice before - the previous year and again just six months ago - he had warned of a war that never happened. And today, there’s a special problem: it is Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. Is Zamir prepared to recommend to the government a full mobilization of the entire nation on the holiest day in the Jewish calendar to face an attack that might or might not happen? Zamir asks questions, and Marwan does his best to reassure him that war is indeed in the offing. He explains how Egyptian troops will cross the Suez Canal over five bridges, advance ten kilometres into the occupied Sinai and stop under their missile umbrella to protect them from Israeli air attacks; meanwhile, Syrian forces will strike in the north and invade the occupied Golan Heights. The time of attack, says Marwan: 6 October, at sunset. That’s just a few hours away.

After nearly two hours, the meeting is over; Mossad agents who follow Marwan can see that he returns to his hotel. Soon after, Zamir and Asherov emerge from the safe flat and hurry to the Israeli embassy. For Zamir this is an agonizing moment as he is fully aware of the ramifications of a massive mobilization of reserve soldiers on Yom Kippur. But he decides that he has no other choice, as to ignore the warning of war he has just received from the man he often describes as `our best spy’ would be irresponsible. So, at 2.30 a.m. on 6 October, in a coded telephone call to Israel, Zamir sounds the alarm.

When Prime Minister Golda Meir, Defence Minister Moshe Dayan, and Army Chief of Staff David Elazar meet in Tel Aviv soon after they receive the warning of an imminent war, they are divided and unsure of what to do next. Dayan, who is directly responsible for the military, is reluctant to order a full mobilization, arguing that, on the basis of a warning from `Zvi’s friend’ (a reference to Marwan), you don’t move everything to war.’ But the prime minister sides with her military Chief of Staff, who insists they should act on Marwan’s warning and mobilize the entire nation - the reserve forces, tanks, artillery, planes, everything. So in the middle of Yom Kippur, as a result of Marwan’s London warning that war was to start soon, Israeli citizens in their thousands are called up. They abandon synagogues, break the fast, put on uniforms, and hurry to the front.

Egyptian forces celebrate the crossing of the Suez Canal

Unlike in 1972 and April 1973, this time, Marwan was correct: Egypt and Syria did indeed launch a massive invasion. Thousands of Egyptian troops crossed the Suez Canal and planted flags inside the Israeli-occupied Sinai. On the Golan Heights, hundreds of Syrian tanks broke through the lines and easily overcame the few Israelis who defended the area, as the bulk of the army - the reserves - was still far away. But whereas Marwan’s London warning was of a `sunset’ invasion, the actual attack came at two o’clock in the afternoon.

COMING SOON …

CHAPTER 4: I UNMASK MARWAN

![Ahro[n]pinion: Israel & Middle Eastern Affairs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa3267808-8a75-4b8a-acfb-53838512afbe_1059x1059.png)